Beyond the Output: Critical Thinking From An Ethical AI Lens

- Michelle Burk

- May 5, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: May 7, 2025

“Dr. Burk, can I ask you a question?”

One of my students, an aspiring video game designer, had finished his work early. As an educator, and student, I've maintained the same ethos for many years: If I finish what I am supposed to do, I should be allowed to do what I'd like to do.

I hold my students to that logic, too. I set a high standard for completion. I need to see their process, their progress, and their work. I need to know that they could replicate the assignment without me. If they can do that, they have earned the freedom to explore.

This student had been working independently on a narrative for a PC game and had stumbled across a website called Neural Blender. The interface looks different now, but it still functions the same. You enter text, and it returns an image.

At the time, I thought it was one of the most incredible things I had ever seen. The student asked me to input the title of my poetry book to see how the model would interpret it. The result was not great. It was a jumbled amalgamation of half-formed objects in colors that did not evoke the content of my work.

Instead of being disappointed, I spent the next ten or fifteen minutes experimenting with different word combinations, searching for something beautiful, unique, and coherent. Even then, even with that early model, I realized something: the tool could produce an output, but it could not substitute for vision. Without precise inputs, aesthetic judgment, and a willingness to keep refining, it simply generated noise.

A year later, in a different classroom, another student approached me with a laptop.

“Dr. Burk, can I ask you a question?”

He shoved the screen toward me as his classmates gathered around.

“Just read this and tell me what you think,” he said.

On the screen was a relatively simple interface. I honestly cannot remember if it even said ChatGPT, but I had seen a headline that morning about an AI tool that was supposedly going to change everything. At the time, I was in what I call a “Containment Phase,” a three to six-month period where I deliberately step back from social media, news, podcasts, true crime stories, and anything overly symbolic or distracting. It's how I reset, and it's entirely necessary for my mental health. But with a phone, it is impossible to fully escape. At this time, my Apple News alerts still popped up, and resisting them became an exercise in self-control.

“Just read it without…?” I asked.

“Yes!” they all said at once. I started skimming.

“In the Pond is a book by… It’s about…”

After four or five sentences, I set the laptop down. “Is this like a sixth grader’s book report on what we’re reading?” I asked. The group chuckled.

We were preparing to read Ha Jin’s In the Pond, a novel about communication, language, and resisting authority. It is a great read, short and sharp.

I skimmed a little more and set the laptop down again.

“They’re not even talking about the right book!” I exclaimed, confused. “Did you get some middle schooler to write this?”

It wouldn’t have been so far outside the realm of possibility. This particular institution was small, with sixth through twelfth grade coalescing in ways that were sometimes unique, sometimes challenging.

“It’s AI!” the student explained excitedly. “AI wrote that!”

That was my first direct experience with a public-facing language model. I could see immediately what had happened. The model had produced something plausible but incorrect. What worried me was that the students had not questioned it. They had not cross-referenced, fact-checked, or interrogated the output. They assumed that because it sounded fluent, it must be accurate.

I told them, “Use this wisely. It is going to be very powerful. But it is also going to be wrong a lot of the time.”

I encouraged them to keep the challenge, rigor, and questioning alive, even when something sounded right.

Later, that same lesson reemerged in my postdoctoral research.

I had been studying figures connected to Jung, including Herbert Silberer. Silberer was an early student of Freud and an overlooked psychoanalyst who crossed into alchemy, mysticism, and dream symbolism. His work was too esoteric for the psychoanalytic establishment, which eventually marginalized him. He was excluded from the official narrative, even though his ideas bridged psychology and spiritual symbolism in ways few dared to explore.

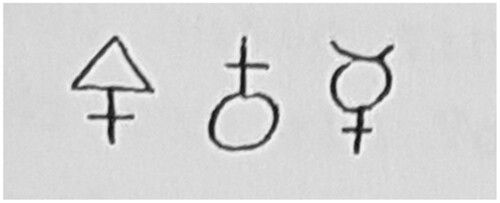

I came across an essay describing symbols that had once adorned Silberer’s grave. The interpretation in the essay claimed the symbols represented “sulfur,” “earth,” and “mercury.” But something about that did not feel right. In alchemical systems, it is rare to double up on an element, and earth was already present simply by the fact of the grave itself. The ritual logic felt incomplete, though the scholar’s work was otherwise sound.

I spent time researching other possibilities, trying to reason out what those symbols might have meant. Could the creators of the glyphs have been signaling that Silberer’s work was unfinished? But why place that message on his grave, reinforcing the incomplete nature of his life? That did not seem like an honorary or alchemically coherent tribute.

Still uncertain, I turned to ChatGPT. I shared my hypothesis, and it generated some possible interpretations, some of which mirrored my own thinking. But I still felt something was missing.

Finally, I uploaded an image of the symbols and asked again.

This time, the AI responded, “Thank you for clarifying. The middle symbol is actually the symbol for salt.”

And suddenly, it made sense. Salt: the purifier, the mediator, the balancing element between material and spiritual realms. The ritual was complete. The meaning locked into place. I followed up with a series of questions, asking it to provide sources and explain why there might have been a misinterpretation, which it did, quite comprehensively. There is some difference in interpretations of that exact symbol, with many contemporary scholars tying it to "earth," while various esoteric texts tie it to "salt." Less of a mistake on the scholar's part, and more a reflection on how context influences understanding.

But notice: it was not the AI that knew. It was the background knowledge, the intuition, the persistence that led me to ask again, to frame the question differently, to seek a better answer.

Even so, believing the AI’s interpretation over that of a scholar invites its own questions. It is less about who is “right” and more about how either party, the AI or the human, can support speculation with evidence. We, as humans, have the added value of being able to explore texts that (hint, hint) may not be digitized yet. We still have the ability to do outside research that exceeds what is possible, even for expansive LLMs.

In each of these moments (the image generator, the book report, the gravestone symbols) the pattern was the same: AI produced an output, but without human discernment, it was not insight.

The tool could only work as well as the inquiry driving it. The beauty, the accuracy, the resonance did not come automatically. It came because I brought critical thinking to the exchange.

There is an intellectual resilience, a rigor (a word contemporary educators often avoid), that is still necessary. If we focus only on ease, we risk erasing the very friction that shapes thinkers, scholars, and artists. Without that friction, we are not generating new knowledge, or practicing ethical AI use. We are simply echoing the machine.

Comments