The Unquiet Tyranny of TikTok's "Group 7"

- Michelle Burk

- Oct 21, 2025

- 6 min read

Upon reading this, the trend will already have passed.

It's only been a few days (three, maybe four?), but TikTok’s “Group 7” phenomenon has already reached the apex of virality. In that brief flicker, “Group 7” managed to reveal a great deal about algorithmic psychology, communal longing, grassroots market research, and the bizarre velocity of online meaning-making.

I Have No Idea What "Group 7" Is...

That's okay. The trend cycle is rapid these days. The meme began on Friday, October 17, when musician Sophia James, known for her 2024 album Clockwork, posted seven consecutive TikToks as part of what she described as “a little science experiment.” Each video featured her music, and she invited viewers to identify which “group” they had been sorted into, depending on which post appeared on their feed. Her objective was simple. She wanted to determine which video received the most reach. Her phrasing, however (“You’re in Group 7, welcome!”) became the catalyst for a communal hallucination.

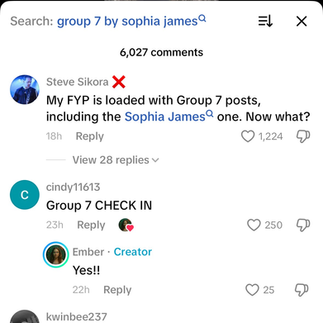

Within hours, commenters on “Group 7” began speculating about what their grouping meant. Why had they been “chosen”? Were they special? What did “Group 7” signify? The seventh video vastly outperformed the others, garnering over 2 million likes and 100,000 comments. Soon, users began creating their own Group 7 content, welcoming “new members,” defining shared traits, and even constructing personality archetypes.

In an interview with The New York Times, James admitted, “In some ways I feel like I’ve learned some things, and in other ways, I’m more lost than when I started.”

That line, almost philosophical in its candor, encapsulates what this fleeting event uncovers about the algorithmic unconscious: a human desire for meaning in the meaningless, and a social instinct to build identity through affiliation, even when the parameters are absurd.

The Aesthetic of Context Collapse

I started getting "Group 7" content two days ago (though not the original post by James). At points, I questioned whether the other groups even existed since I still haven't seen anything from Groups 1-6. It seemed like some Group 7 content was self-aggrandizing and with (slightly unearned) self-congratulations. At other points, the algorithm pushed "Group 7" content of waterfalls, soothing imagery, and short lectures on metaphysics. These are all things that I am, in fact, interested in, which made me wonder how widespread inclusion in "Group 7 "was since I was also shown content in which I have zero interest.

One of TikTok’s defining stylistic traits is context collapse: the erasure of narrative continuity between videos. A user may see a response to a meme before seeing the original post, forcing them to reconstruct meaning in reverse. “Group 7” flourished within this dynamic. Many users first encountered “response” videos like people welcoming others to the group, joking about its mystique, before ever seeing James’s initial post.

This created a feedback loop of confusion-as-engagement. Each user sought to clarify the premise, generating yet more content about the mystery itself. In essence, the algorithm learned that uncertainty drives attention, and it rewarded that uncertainty accordingly.

In semiotic terms, “Group 7” is a floating signifier: a term that signifies everything and nothing, adaptable to each user’s projection. Some see it as whimsical, others as metaphysical, others as commentary on digital fate. The algorithm doesn't really care; it only recognizes sustained engagement, and perhaps it is that members of "Group 7" have the most sustained engagement.

Algorithms shape identity through feedback, not intention. The traits that appear to define “Group 7 people” (calm, artistic, reflective) were not encoded by James but inferred by the system through each user’s own digital habits. Marketing now functions as anthropology and virality serves as a real-time ethnographic lens into how people self-organize, affiliate, and mythologize online.

Belonging By Design

At first glance, “Group 7” feels trivial. Some users have even called it outright “stupid.” Its psychological gravity lies in its exploitation of the oldest social reflex: the need to belong. To be “in Group 7," rather than outside it, offers the small thrill of inclusion in an exclusive collective.

Comment sections are full of people declaring pride in their membership or debating what distinguishes them from other groups.

The fact that a sense of camaraderie and community can be easily forged around a shared grouping, even sans context is, in some ways, encouraging. At the same time, to be told that you're part of an exclusive group, shown content for that group, and to become a representative of an affiliation without much force has significant implications, many of which have come to pass in the 2020's.

“Group 7” exposes both the brilliance and the absurdity of our algorithmic age because community is now algorithmically assignable. Meaning is emergent, not intrinsic. Users construct significance retroactively, often through collective storytelling.

It mirrors the logic of fan cultures, sports fandom, and brand communities, all of which rely on an affective contract rather than a rational one. Participants bond and connect around shared symbols, colors, slogans, and lore. “Group 7” demonstrates how easily the architecture of belonging can be manufactured.

The Algorithm As Oracle

TikTok’s recommendation system (the opaque “oracle” that governs who sees what) is designed to personalize, not to explain. Its core logic relies on three types of signals: user interactions (likes, shares, comments, watch time), video information (hashtags, sounds, captions), and user data (language, device, location). It is not built to convey intent, only to optimize attention.

When James’s seventh post began outperforming the others, the algorithm likely amplified it further, creating a positive feedback loop: higher engagement triggered wider reach, which in turn attracted more engagement. The very important catch here is that because this system offers no narrative (no why) users filled that void with myth. They imagined a secret selection mechanism, a deeper pattern behind their inclusion in “Group 7.”

This is algorithmic apophenia: the tendency to perceive meaningful patterns in random data. It is also participatory anthropology, as users collectively theorized their own categorization.

“Group 7” thus became a microcosm of how people interact with recommendation engines in general: not as neutral distribution systems, but as inscrutable judges of identity and belonging.

Feedback Loops and the Psychology of Virality

In systems theory, a positive feedback loop amplifies deviations; each output feeds back into the system as input, creating exponential growth. Virality on TikTok operates precisely this way. Once a piece of content crosses a certain engagement threshold, it enters a self-reinforcing cycle that multiplies visibility until the content is oversaturated or no longer valuable.

Conversely, negative feedback loops stabilize systems by dampening deviation, such as when overexposure leads to fatigue, mockery, or counter-memes.

"Group 7" is at its peak precisely because the parodies have started (“Group 8 supremacy,” “Justice for Group 3”). There’s also a subtle irony here since users who publicly mock “Group 7” for its meaninglessness still participate in its perpetuation through satire, critique, and meta-commentary.

Oh, and now the brands have entered the chat. Everyone from Gain to the Kansas City Chiefs have posts dedicated to “Group 7.”

Every viral moment contains the seeds of its own decline. Once a brand virtue signals the validity of a trend, its authenticity becomes muted. It’s good to be recognized by bigger entities, but there’s an underlying knowledge that this inherently signals the trend’s visible move from authentic to branded and curated.

The Aftermath of a Digital Experiment

Sophia James’s experiment was modest in design, but its outcomes were sociologically rich. It demonstrated that the internet no longer requires substance to generate structure. A sense of belonging, even to something arbitrary, remains intoxicating. For creators, this project also doubles as a form of grassroots market research. James’ experiment unwittingly mapped out which types of framing (“You are part of something”) drive higher engagement. Brands and marketers have long known that people are more likely to engage with narratives that affirm identity or exclusivity. “Group 7” did in three days what consumer psychologists spend months testing: it revealed the emotional triggers of the digital collective.

The challenge is that the emergence of generative tools has made it far easier to propel imagery or narratives into the general population via social media in more covert ways. I’d love to believe that there’s no nefarious or mediate facet to James’ experiment, because this kind of grassroots experimentation can be revolutionary. After all, it creates an egalitarian space where the public can examine and consider algorithmic pathways that have been previously obscured.

I’ve written about this before, but we like the illusion that we’re not being mediated; we want to feel (even though social media’s implicit project in 2025 is to generate revenue) that we’ve encountered and organically recognized and popularized something worthy. In our current moment, which is slowly approaching AI-exhaustion, worthiness becomes tantamount with authenticity.

Naturally, the next question would be: authenticity by whose standards?

Comments